#zennor quoit

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hallam Tower Hotel, Sheffield

Lanyon & Zennor Quoit, West Penwith, Cornwall.

729 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Zennor Quoit' Prehistoric Burial Chamber, Penzance, Cornwall.

#ice age#stone age#bronze age#copper age#iron age#neolithic#mesolithic#calcholithic#paleolithic#prehistory#prehistoric#burial chamber#burial mound#burial ground#megalithic#megalith#quoit#creative#education#cross arts#cross curricular#community#identity#belonging#ritual#archaeology#cornwall

231 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Porth Nanven, Andrew Palmer

The large, smooth boulders which populate the beaches of Porth Nanven Cove have led to its being referred to by some as ‘Dinosaur Egg Beach’. The black boulders were used to line the vaults of the Bank of England. Cape Cornwall has an ancient and elemental atmosphere about it which is especially encapsulated by Cot Valley and the magnetic beach at Nanven which lies at its mouth. Celtic settlements, stone circles and quoits abound along with the abandoned tin mines which draw me back to explore and interpret the power of nature, especially where the land meets the sea. In this painting I was inspired by the particular way in which the waves broke over the egg shaped rocks and the dramatic but smooth and sensuous emotion that that meeting provoked in me. I spent some time camping near Zennor and made many 'plein air' studies on the spot encapsulating the varied moods that the sea, the land and the weather created. My spiritual interaction with them guided the interaction of - oil paint, linseed oil and paste, turpentine, coarse brushes, squeegies, sand, seaweed and all the elements, to create images which I then worked with in my studio in Port Gaverne, on a one metre square canvas, quite quickly in this instance , to produce this painting 'Nanven'.

https://www.saatchiart.com/art/Painting-Porth-Nanven/393643/3054517/view

0 notes

Text

Chun Quoit, one of Cornwall’s best preserved prehistoric monuments, is spectacularly located high on a hill in West Penwith. Leaning with your back against it’s sun-warmed stones you can see for miles, expansive views across moorland, farmland and out to sea. But what was this structure for and what did it represent to the people that built it?

“Chun Cromlech, it is not so large . . . but its lonely position on the shoulder of the hill makes it an impressive object” – A.G. Folliott-Stokes, 1928.

Cornish Quoits

Cornwall’s quoits are some of our most imposing and easily recognisable monuments. There are around 20 remaining in the region, mostly clustered in Penwith. Besides Chun Quoit they include Lanyon, Mulfra, Zennor, Trethevy and Carwynnen – old Cornish names that feel suitably ancient and transportive.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

At one time there were almost certainly many more of these monuments across the region. As Ian Soulsby theorises:

“The fate of the Devil’s Coyt (a dialect spelling form) near St Columb Major, enterprisingly used as a pigsty until it collapsed in the 1840s, and then used as a source of hedging stone, reminds us that they [quoits] were probably much more numerous, like countless other types of early Cornish monuments.”

The earliest name recorded for these prehistoric structures in Cornwall is Cromlegh in an early 10th century charter for St Buryan. (Crom meaning curved, legh meaning slab in Cornish.) This word is closely related to the Welsh equivalent, ‘Cromlech‘. Where the term ‘quoit’ comes from isn’t entirely clear. Some believe the name has a connection to the game ‘Quoits’, others that it comes from a Cornish dialect word.

Caitlin Green, a historian who specialises in early literature, helped me to decipher the etymology further. Although Caitlin isn’t sure when the word was first used in Cornish, it likely comes from a Welsh word meaning ‘discus’, a solid circular object thrown for sport. Quoit “derives from the Anglo-Norman ‘coite’ borrowed into English in the 14th/15th century and implies they were seen as huge discuses thrown by giants.”

The folklore in Cornwall associated with these monuments varies from quoit to quoit but Robert Hunt reported that as a whole they were considered sacred and untouchable.

“It is a common belief amongst the peasantry over every part of Cornwall, that no human power can remove any of those stones which have been rendered sacred to them by traditional romance. Many a time have I been told that certain stones had been removed by day, but that they always returned by night to their original positions, and that the parties who had dared to tamper with those sacred stones were punished in some way.”

Resting Places

Dolmens, cromlechs, quoits, hunebedden, dolmains, anta, trikuharri – there are many names for these stone structures which can be found in one form or another all across Europe, in Central Asia and as far away as Korea. The translation of the various names ranges from ‘stone table’ to ‘bed of giants’. Almost universally however they are considered by archaeologists to be funerary structures, places where our dead ancestors were laid to rest.

Hunebedden, Netherlands. Credit: Entoen.nu

Although the design of this type of monument varies greatly from region to region but in the main they are constructed from three or more uprights supporting a large capstone. Burials or cremations were then thought to have been deposited within the void.

It was thought that these megalithic frames were once covered with an earthen mound which was subsequently eroded away by the elements, but apparently that is no longer agreed upon by archaeologists.

It seems possible that the stone structures were built to be free standing. Many dolmans, such as Chun and Mulfra, do stand on a low platform of stones however.

The chambered tombs of Cornwall are some of our oldest surviving monuments and Chun is one of the best preserved. Accurately dating quoits is difficult, however, due to the lack of finds, but they are thought to have been constructed during the middle to late Neolithic, around 3500 – 2500BC. This makes Chun Quoit 4000 – 5000 years old roughly the same age as the Pyramids at Giza.

Alternative Explanations

With ancient history there is rarely one definitive answer. In all honesty all we are ever doing is making educated guesses about what some structures were and what the people who built them intended. Throw into the mix the possibility of changes in use over the centuries that followed and it is little wonder that there are often varied and conflicting interpretations of prehistoric monuments. Quoits are no different.

“These structures, which seem to have been much more than mere burial mounds, probably fulfilled a number of ceremonial and territorial roles.” – Ian Soulsby

Although most archaeologists would agree that quoits are tombs, that they were “stone structures in which the dead were laid”, some argue that this may not have been their sole function.

Peter Herring, a landscape historian and archaeologist working for Cornwall Council, suggests that quoits could have had many different functions beyond funerary. They could have been communal gathering places, they perhaps marked very early territories or may have been the focus of ritual and spiritual practices.

John Barnett also suggests that these monuments could have been territorial markers seen from a distance and that their imposing size could be in part intended to impress visitors or those taking part in ceremonies:

“. . .the frequent burials perhaps indicate the concept of an ancestral resting place that would have been central to the symbolic expression of territory. In areas where settlement was relatively dispersed with no ‘secular’ centre, this symbolic centre could become the most important place there is and would serve a number of ceremonial functions . . . “

Stuart Dow, a prolific dowser, creator of the Earth Energies, Alignments and Leys Facebook group and a dear friend, has another slightly different take on these sites.

“They are devices to focus and harness the earth’s energies . . . every dowser has found them to be, if you like, a ‘hot spot’. The burials came later when they became forgotten as devices but remembered as something very special erected by their ancestors. Chun quoit is a great example, the radials of energy coming from [it] are phenomenal.”

Stuart Dow’s map of the energy lines at Chun Quoit

Another local fountain of knowledge Cheryl Stratton points out in her book Pagan Cornwall that there have been reports of a strange light phenomena seen dancing along the edge of Chun quoit itself. I will leave the rest to your own personal interpretation.

Beautiful Chun

“Chun cromlech . . . rises with great effect from the rock strewn moor. It stands on a little tumulus and is as prefect as when erected.” – Murray’s Handbook for Devon & Cornwall, 1859.

The name Chun is believed to be a contraction of the Cornish Chy Woon meaning ‘the house on the down’. This quoit may be one of Cornwall’s smallest but it is in a remarkable state of preservation. Writing in 1897 John Lloyd Warden Page thought it “the most perfect of the cromlechs” and it seems to have altered little since.

Chun quoit is known as a portal dolmen. It is constructed of four mighty uprights and a capstone which is roughly 3.7m (12ft) square and 0.8m (2.5ft) thick. There are two upright stones on the east and west sides, one on the north and a forth non-supporting stone on the south side completing the boxed chamber.

“The Capstone is nearly round, and as it’s top is convex and it projects considerably over the four supporting stones, which are set close together forming a square chamber, the whole structure looks at a distance like a giant mushroom” – John Lloyd Warden Page, 1897

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Chun quoit is around 4000 years old and interestingly stands close to an ancient trackway. The route is known as the Tinner’s Way and has been in use since at least the early Bronze Age but is almost certainly older. It ran between the area near St Ives to the known Neolithic axe factories on the western cliffs near Kenidjack Castle.

In 1871 when Borlase excavated Chun quoit, he describes surrounding mound and stone platform as being 9.7m in diameter and surrounded by a kerb of small upright stones. He found nothing inside the chamber of the quoit itself. Other features of interest included a possible cist identified within the mound and a line of cup marks on the surface of the capstone, possibly from the Bronze Age. Both may indicate the importance the site held for local people for generation after generation.

Surrounding Landscape

No monument exists in isolation, and Chun Quoit is no different. Close by you can find Boswens Menhir, Men-an Tol, Tregeseal Stone Circles, Lanyon Quoit, Boskednan Stone Circle and many others. But the most obvious neighbour is Chun Castle built during the Iron Age.

Entrance to Chun Castle

This impressive and complex site was built long after the quoit and deserves a post all of its own which is why I won’t cover it in detail here.

Chun Downs on which the quoit and castle stand is an atmospheric place like so much of the Penwith, a place where it is easy to imagine strange events and mystical beings at large.

“On the plain beneath Chun castle are scores of small barrows, heaps of stone, piled about the height of three feet. Some have been opened no urns or bones were found, but the earth was discoloured as if it had been subjected to fire. They lie scattered about in all directions, as if there had been some fierce battle here, and the dead had been burnt and their ashes buried on the spot where they had fallen.” John Thomas Blight, 1861.

Blight’s description suggests that Chun quoit is part of a far larger ceremonial or funerary landscape. The hill around the quoit is often deeply covered in deep undergrowth so I have personally never noticed any small cairns. But thirty years after Blight, Warden-Page also noted these features:

“The cromlech was evidently the chief tomb among many smaller ones, for the hillside is covered with the remains of tumuli.”

A Sorry Tale

In April 1939 The Cornishman newspaper reported, as a part of an article sharing ‘old timers’ memories, a strange and tragic event that had occurred eighty years before.

According to the paper in around 1859 there were two elderly sisters living in a thatched hut near Chun Quoit. The Riddigan sisters also owned some land and another cottage on the downs rented by a man named Lavers.

Lavers fell behind on his rent and in an attempt to avoid paying he perpetrated an act of cruel desperation. One night he set fire to the sister’s hut and his own cottage and fled. The two women died in the fire. According to the article a field close to the quoit was from then on known as ‘Burnt House’.

Final Thoughts

I have been visiting Chun Quoit for more than twenty years and have always assumed that it was the site of an ancient burial but what I have learnt while preparing this post has opened my eyes to so many other possibilities. Chun has taken on a different much more complex personality for me now. It just goes to show that there is always more waiting to be discovered about these wonderful prehistoric sites!

There are pages still waiting to be turned.

Further Reading:

Carn Kenidjack – the Hooting Cairn

Zennor Head

Thoughts of Carwynnen Quoit

Chun Quoit Chun Quoit, one of Cornwall's best preserved prehistoric monuments, is spectacularly located high on a hill in West Penwith.

0 notes

Photo

R. T. Pentreath

Engravings from Archaeologia Cambrensis

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zennor Quoit,

West Penwith, Cornwall.

June 23.

223 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Zennor Quoit' Prehistoric Dolmen, Zennor, Cornwall, 23.7.19.

A first visit for me and quite a surprise.

Perhaps one of the least visited of the Cornwall Prehistoric Quoits, Zennor is a monster and largely intact. At some point in the last few hundred years there was an attempt at turning it into a cattle hut and hence the strange arrangement of standing stones where the forecourt should be. The capstone is massive and it's an impressive sight up close. Worth the visit!

#ice age#stone age#bronze age#copper age#iron age#neolithic#mesolithic#calcholithic#paleolithic#prehistory#Prehistoric#megalithic#megalith#monolith#burial chamber#burial grounds#dolmen#quoit#cornwall#creative#education#cross arts#cross curricular#community#identity#belonging#ritual#archaeology

195 notes

·

View notes

Photo

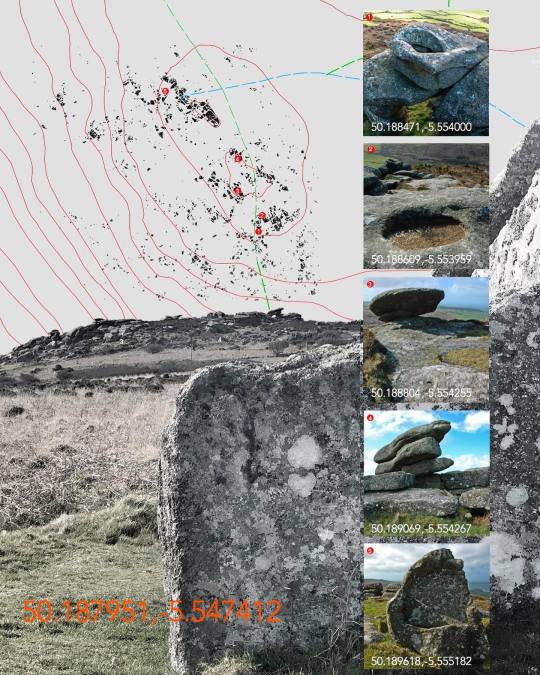

zennor quoit. dolmen are amongst the earliest monuments to appear on the penwith peninsular with their careful positioning within the landscape. this one on the plateau below and east of zennor hill and south of the outcrops and quoit at sperris. zennor hill contains many unusual stones, a holed stone similar to the one used at the men-an-tol stone circle, a balancing stone known locally as a logan stone, a propped stone recently identified, all appear on the hills silhouette as seen from zennor quoit. all undoubtably important those that built the quoit and echoed in its form. dolmen appear all along the atlantic seaboard all the way up the western coast of england wales across ireland and the north west land central scotland and connects it to the migratory routes of the first farmers. although associated with burials they are considered to have multi-purpose uses, rather more in spirit of shrines or the ancient greek agora, where people gather to venerate the ancestors and the changing seasons; places of interaction and exchange. . . . #neolithicbritain #neolithic #firstfarmers #agriculture #quoits #zennorquoit #dolmen #ancienthistory #ancientlandscape #proppedstones #loganrock #balancingstones #holedstones #men-an-tol #menantol #gatheringplaces https://instagr.am/p/CNPi_l-rGQr/

1 note

·

View note

Text

Carn Cottage & Zennor Quoit, West Penwith, Cornwall.

23/6/23

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

zennor hill towards sperris croft and quoit. the germans have a better word than the (romantic overtones of) english landscape - landshaft or land shape. important now as it undoubtedly was for our ancestors throughout prehistory. . . . #ancienttimes, #ancientlandscape, #landshaft, #theshapeofstones, #landshape, #ancientwisdom, #memoryspace, #orienteering, #songlines, #memorytrails, #tors, #carns, #stonestories, #neolithictransition #mesolithicneolithic, https://instagr.am/p/CT1sKsGo_g9/

0 notes

Photo

zennor hill looking towards zennor quoit. ‘the tors were not only their source of inspiration, but they were constructed in the form of tors. in elevating large stones, these people were emulating the work of a super-ancestral past. the dolmens, in effect, were the tors dismantled and put back together again to resemble their original form. once constructed, they could themselves be tors’…(TILLEY) solutions or rock basins on the upper surface of tor stones form over many millennia by the continual agitation of rain water combined with the acidic action of sediments within the rock to create deep circular depressions that can penetrate right through the rock (see previous post). these are found all over the granite tors of west penwith in close proximity to the megalithic monuments. borlase was the first to recognise the significance they had in the eyes of our ancestors as ‘sacred’ basins of water, perhaps seen by them in turn, as the ceremonial ‘art’work of their ancestors. this view shows zennor quoit (centre) set against trink hill on that appears just above the horizon from the vantage point of the rock basin. #solutionsbasin, #rockbasin, #ancienthistory, #ancientrituals, #sacredwater, #sacredwaters, #quoits, #zennor, #zennorhill, #zennorquoit, #megalthic, #ancientmonument, #ancientwisdom, #tors, #granitetors, #westpenwith, #megaliths, #montagecity.com, https://instagr.am/p/CSbtcS4I-8b/

0 notes

Photo

‘slabs that have toppled from the top of the rock stacks... rest horizontally or vertically against their sides, creating slanting roofed chambers large enough to enter and walk through’. (TILLEY). the proximity of zennor and sperris quoits raises the possibility that these emblematic rock formations were the precursors to these early monuments and were deliberately mimicked by their builders. this possible propped stone sits across two large tor stones creating an effective chamber. it seems that the careful curating of a found or given tor formation was readerly transformed by the judicious addition of a ‘capstone’ propped up at one end by a smaller bolder. ____________ things found; things altered; things mimicked. isn’t this redolent of modernist art practice? #balancingstones, #proppedstones, #loganstone, #torstacks, #tors, #capstone, #chamberedtomb, #dolmen, #quoits, #ancientsites, #ancientwisdom, #ancientmodern, #ancientmodernism, #zennorhill, #westpenwith, #foundobjects, #foundrealty, #alternativereality, #transformedreality, #mimesis, https://instagr.am/p/CSP5sdbo5TD/

0 notes

Photo

zennor hill. zennor quoit. constructed image. exploring the stones from zennor hill and their relationship with the quoit. significant stone features make up this extraordinary selection of tors: a holed stone(1) seen on the extreme left of the photo, is the result of acidic rain water oscillating in small depressions in the rock over millennia. this one still in place but one similar converted by the neoliths and included in the ing monuments; men-an-tol and cram brea. logan or balancing stones (2)(3) one with a large solutions basin and one looking like the capstone of a quoit. a propped stone (4) thus one recently classified as such, is now a recognised,fairly new, monument type. another such monument sits between the main tor stacks at carn galva and has an orientation towards the winter solstice sunset. and finally, although not viable from the quoit is a recently discovered ‘sunstone’ (5) that projects the suns rays each midday across its surface giving a different position in line with the changing seasons. it is in fact a very large upturned solutions basin repositioned so the that the original base of the basin is set 5 degrees off the vertical. on its southern edge a small hole penetrates its rim, making a ‘lens’ to project the sun rays. all making a this tor landscape of particular significance. the siting of the quoit in sight of this conglomeration of stone settings is clearly very intriguing. #stonefeature , #stonefeatures , #ancientwisdom , #landscapeart, #naturalstone, #naturalstonefeatures , #solutionsbasin , #waterbasin , #proppedstone , #archeaology , #sunstone , #loganstone , #quoit , #dolmen , https://instagr.am/p/CNX4pVvr73U/

0 notes

Text

In wandering over some of the uncultivated tracts which still maintain their wilderness . . . against the march of cultivation, we are certain of finding rude masses of rock which have some relation to the giants. The giant’s hand or the giant’s chair or it may be the giant’s punch bowl excites your curiosity. What were the mental peculiarities of the people who fixed so permanently those names on fantastic rock masses? What are the conditions, mental or otherwise, necessary for the preservation of these ideas? – Robert Hunt, 1896.

Legends of giants permeate the Cornish landscape. These legendary personages are prolific and dynamic. Cornish giants are often used to explain the unexplainable. To account for an unusual geological phenomena such as the Cheesewring or perhaps the baffling stony remains left behind by our ancestors, like Trethevy Quoit.

Giants built giant walls, carved out giant-sized seats or threw giant boulders like bowling balls. They left their giant footprints and buried their giant hearts.

On Carn Brea hill near Redruth there is a Giant’s coffin, a Giant’s head and hand, the Giant’s wheel and the Giant’s cradle. According to folklore all were the property of a giant known as John of Gaunt, one of the last of his kind.

John is not quite as cool a name for a giant as many of the other Cornish giants. Bolster, Trecobben, Wrath, Blunderbore, Rebecks or Cormoran.

But the real question is what are the origins of these larger than life characters?

A Compact and Bijou Nation

Someone suggested to me recently (now don’t get offended) that the Cornish tend to be rather short in stature. Short, stocky, dark hair. More of a stereotype these days perhaps? But in the past did this more diminutive trait lead somehow to this plethora of legends about giants in Cornwall?

In the anthropologist John Beddoe’s book, The Races of Britain, published in 1885 the Cornish are described as ‘a stalwart race’. Loyal, reliable and hard-working.

“Superior to the Devonians in stature and length of limb . . . Cornwall probably gave the last refuge to the free British warriors, who were gradually forced back by the West Saxons into the peninsula . . . The Cornish are generally dark in hair and often in eye: they resemble the Scottish Highlanders in their warmth of colouring . . .”

So we were taller than the Devonians apparently, (more attractive obviously) but still not exactly blessed with height. Beddoe concludes that the average height of the Cornishman, from his survey of over 300, was around 5ft 7ins. The overall average height for men in the UK is around 5ft 9ins.

There was a theory batted around in the 19th century that Cornwall had been a refuge for the pre-Celtic people of England.

During the Celtic invasion the Neolithic or Pre-Celtic people were a short dark race of an imaginative temperament. The incoming Celts were a much bigger race, broad headed and fair and to the aborigines appeared big men . . . Giants. – J Hambley Rowe, Cornish Notes & Queries, 1906.

This idea that the Cornish were towered over by invaders seems quite common. So could this be the origin of Cornwall’s giants?

It is sometimes supposed that the numerous Cornish giant legends may originate from the Anglo-Saxon, and later Norman, overlordship . . . Cornishmen are relatively small and the foreign invaders probably loomed large by comparison. – Tony Dean and Tony Shaw, The folklore of Cornwall, 1975

Cormoran, illustration by Arthur Rackham

Cornwall’s Real Giants

Not far from the Lands End there is a little village called Trebegean, in English the town of the Giant’s Grave. Near whereunto and within memory certain workmen searching for tin discovered a long square vault containing bones of an excessive big carcase [sic] and verified this etymology of the name.

The above was written by Richard Carew in 1602 and his is not the only account of a real life Cornish giant.

More than 150 years later in 1761 tin miners unearthed something equally strange in the village of Tregony. They accidently dug up a coffin. And this was no ordinary coffin, it was 11 feet (3.5m) long. While any other remains appeared to have crumbled to dust a single tooth was found inside. It measured two and a half inches in length. It was assumed that the miners had found the grave of an actual giant.

You see in Cornwall the giants aren’t just the stuff of legend. There are one or two who have made it into the parish registers too.

• Charles Chilcott

Charles Chilcott was born in 1742. He was what was once known as a ‘gentleman farmer’ and he lived near Tintagel. Charles was big. In his day he was well known for his gigantic stature and feats of extraordinary strength. These days anyone over 6′ 8″ tall is officially classed as a giant. Charles was 6′ 9″ (203cm) and weighed 32 stone or 208 kilograms. This was in a time when the average height was considerably shorter.

Charles lived a pretty uneventful life. His father William had died when he was 3 years old. In August 1768 he married Mary Jose and the couple went on to have two children. Langford, his son born in 1769 and Rebecca, his daughter in 1771.

Their house, Treknow, also known as Tresknow or Trenaw, was actually mentioned in the Doomsday Book. And Charles inherited the property from his mother Rebekah after her death. He lived out his life there, dying in 1815. He was then buried in Tintagel churchyard. Such was his fame locally that his death was reported in the West Briton newspaper:

Died last week at Trenaw, in the parish of Tintagel in consequence of an apoplectic [sic] fit a person commonly known by the appellation of Giant Chilcott. His height was 6 foot 4 inches without shoes. He measured around the breast 6 feet 9 inches. Around the full part of the thigh 3 ft 4 inches and weighed about 460 pounds. He was almost constantly smoking. The stem of the pipe he used was about 2 inches long and he consumed 3 pounds of tobacco weekly. One of his stockings held 6 gallons of wheat. The curiosity of strangers who came to visit him gave him evident pleasure and his usual address on such occasions was “come under my arm little fellow”. – 14th April 1815

Another real life giant was John Laugherne of Truro. He was 7ft 6in tall and known as ‘Long Laugherne’. During the Civil War he fought for the royalist cause as a lieutenant in the Calvary Regiment. It is said that it took more than two strong men to pull his sword from one of Plymouth’s gates when the Cornish Royalists laid siege to the town.

• Anthony Payne

By far the most famous giant (real one anyway) in Cornwall is Anthony Payne. Payne was born in Stratton, near Bude in 1612 and was a sporty lad who grew to be 7’4″ tall (223.5cm) and 32 stone. A great bear of a man he was also quick-witted and gentle.

Anthony Payne

Anthony became the bodyguard of a local notable, Sir Bevill Grenville, and fought along side him during the Civil War. His loyalty and bravery gained him the attention of King Charles who ordered the portrait above, now hanging in The Royal Cornwall Museum, to be painted.

There are many stories about his formidable size and great shows of strength, such as carrying his friends up the steep cliffs near Stratton for a bet, one tucked under each arm. Making him a jerkin (a waistcoat) took three whole deer skins as his chest was so large. But perhaps the most poignant story is that when he passed away at his home in Stratton in 1691 the coffin was too large to fit down the stairs. They had to cut a hole in the floor and lower him out that way. It then took a relay team of strong bearers to carry him to his final resting place.

A Gentle Giant

The legends associated with Cornwall’s Giants are many and varied. There was Bolster the bane of St Agnes is life, Wraft the terror of the St Ives and Porthreath fishermen. Cormoran and his wife Cormelian who lived at St Michael’s Mount and Blunderbore and his brother Rebecks who rampaged around Ludgvan.

But perhaps the most moving story is that of the kindly giant Holiburn. He was a friend to humans and spent his life protecting the people of Morvah and Zennor.

Holiburn the kindly giant

But one day, while playing some game with a local man, Holiburn affectionately patted him on the head and accidentally squashed him completely flat. When the giant realise what he had done he was devastated and cried:

“Oh my son, my son why didn’t they make the shell of thy noodle stronger?”

Holiburn pined away and died of a broken heart. Interestingly there is still a large stone near Morvah church known as the Giants Grave.

The Bones of Prehistoric Beasts

In 1906 an unusual but perhaps logical explanation was offered by Rev. D Gath Whitley for the stories of huge bones often offered as proof of the existence of giants in the past.

At a meeting of the Royal Institution of Cornwall he said:

It has been proved . . . that many of the bones which were formerly said to have belonged to giants in different countries of Europe are simply the remains of the mammoths and the rhinoceros.

Mr Whitley quoted instances in France, Germany, Spain and Russia where the discovery of enormous bones had been taken as evidence of a race of extraordinary men. These had then later been identified by anatomists as the remains of ancient elephants or even whales. Whitley explained:

In prehistoric days many of the bones of the elephant, rhinoceros and hippopotamus were found in Cornwall by the rude primitive inhabitants and were by them considered to have belonged to a race of gigantic human beings.

Whatever the roots of our many Cornish giant legends the landscape and folklore of Cornwall is far richer because of them. And I for one am beyond grateful that our ancestors were such an imaginative bunch!

Further Reading:

The Giant’s Heart

Zennor Head

Real Cornish Giants, where legends begin In wandering over some of the uncultivated tracts which still maintain their wilderness . . . against the march of cultivation, we are certain of finding rude masses of rock which have some relation to the giants.

0 notes